A sensitive HPTLC-EDA method using a 4-MU fluorescent probe for AChE inhibitor screening

The research group at Université Clermont Auvergne (ICCF, CNRS, Clermont-Ferrand, France) works at the interface of analytical chemistry, enzymology, and natural product research. Their activities include the development of innovative HPTLC-based Effect-Directed Analysis (EDA), phytochemical profiling, and biological evaluation of bioactive metabolites.

Introduction

Effect-Directed Analysis combined with HPTLC is a powerful technique to locate bioactive substances in complex matrices. However, traditional chromogenic agents, such as the 1-naphthyl acetate/Fast Blue Salt (FBS) system, often lack sufficient and can produce artefacts that make bioactivity interpretation difficult.

To overcome these limitations, a new fluorogenic probe was developed based on 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) for the detection of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors on HPTLC plates. The probe’s acetylated form, 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate, is non-fluorescent until enzymatically cleaved, producing a bright fluorescent signal with improved linearity and significantly lower detection limits.

Validated according to ICH guidelines, the method provides more than a threefold improvement in sensitivity compared to the classical chromogenic system and was successfully applied to complex natural extracts.

Standard solutions

Galantamine was used as the inhibitor reference standard. It was prepared by dissolving 2.0 mg in 10.0 mL of methanol, followed by consecutive 10-fold dilutions to obtain final concentrations of 20 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL.

Sample preparation

Freeze-dried mushroom samples were extracted with methanol at a concentration of 5.0 mg/mL.

Chromatogram layer

HPTLC plates silica gel 60 F254 (Merck) 20 x 10 cm were used.

Sample application

Sample solution volumes were adjusted to deposit 50 μg of extract per application. Galantamine standard solutions were applied in volumes corresponding to 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50 ng per application.

The solutions were applied as bands using the Automatic TLC Sampler 4 (ATS 4), with 15 tracks, a band length 8.0 mm, a distance from the left edge 20.0 mm, a track distance 11.4 mm, a distance from the lower edge 8.0 mm.

Chromatography

Plates were developed in the Automatic Developing Chamber 2 (ADC 2) with chamber saturation (with filter paper) for 20 min and after plate activation at 33 % relative humidity for 10 min using a saturated solution of magnesium chloride, to a migration distance of 70 mm (from the lower edge), followed by drying for 30 min.

For the proof of concept, galantamine standard was initially developed using chloroform, methanol, 30 % ammonia solution 93:5:2 (V/V) as developing solvent.

For the case study using mushroom extracts, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, formic acid, acetic acid, water 100:25:10:10:11 (V/V) was used as developing solvent.

For plates where an acidic mobile phase was used, neutralization was performed by exposing the plates to ammonia vapor for 5 min, followed by drying for 30 min under a stream of cold air using the ADC 2.

Post-chromatographic derivatization (HPTLC-EDA)

The substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate was synthesized in one step by acetylation of 4-methylumbelliferone, yielding a pure, non-fluorescent derivative suitable for plate derivatization.

1. Pre-moistening:

1.5 mL TRIS-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8) was sprayed using the TLC Derivatizer (blue nozzle, spraying level 6).

2. Enzyme application:

1.5 mL of solution containing 25 U of AChE and 1.5 mg BSA in TRIS-HCl buffer was sprayed (blue nozzle, spraying level 6).

3. Moistening:

An additional 1.0 mL of TRIS-HCl buffer was sprayed to reach full saturation of water in the plate.

4. Incubation:

Plates were incubated for 25 min at 37°C in a humidity chamber.

5. Substrate application:

Traditional method: spraying 750 μL of solution containing 250 μL of 1-naphthylacetate in ethanol (3 mg/mL) and 500 μL of fast blue salt in water (3 mg/mL).

New method: 750 μL of 4-methylumbelliferone acetate (1.5 mg/mL in 2:1 ethanol/water) was sprayed using TLC Derivatizer (blue nozzle, spraying level 6).

6. Final incubation:

Plates were incubated for 20 min in a moistened box and then dried under a cool air stream for 5 min before documentation. Plates derivatized using the traditional method were dried on TLC Plate Heater 3 at 120°C for 2 min.

Documentation

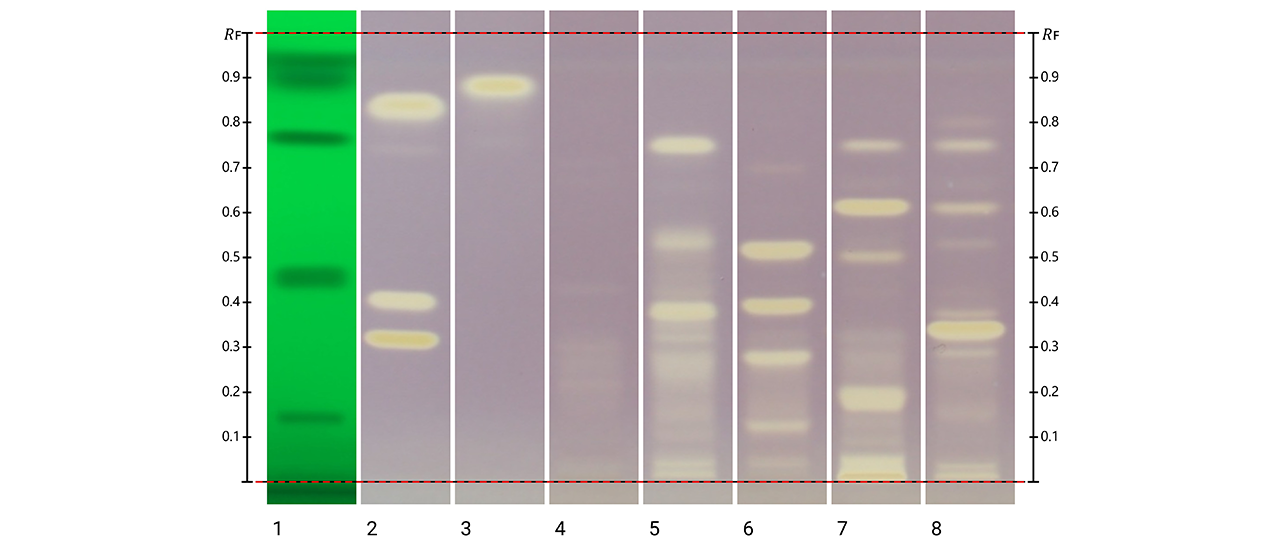

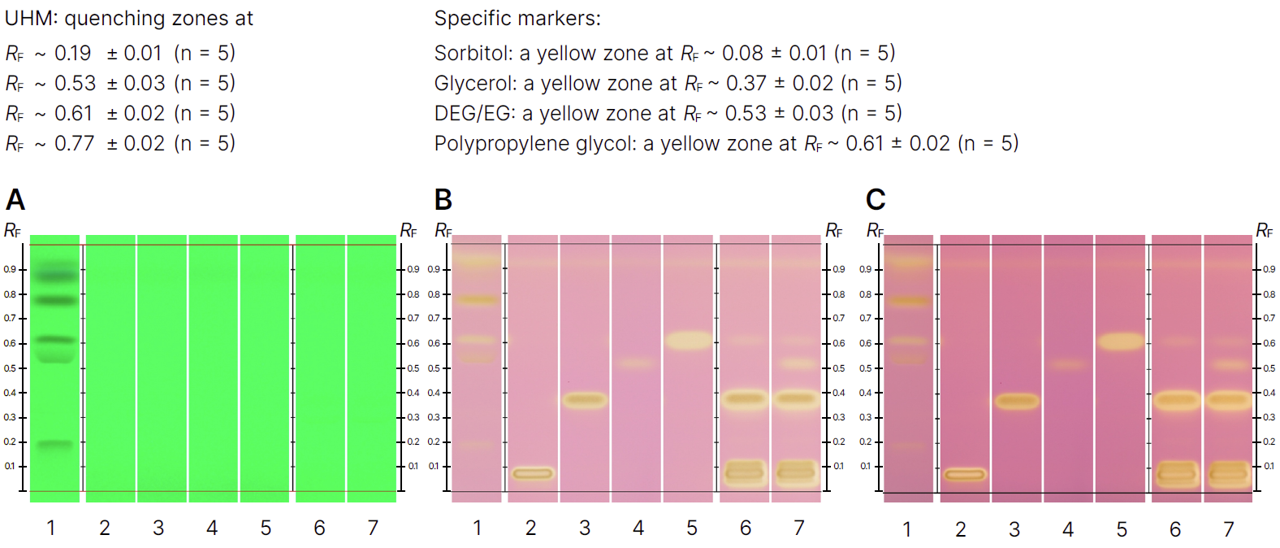

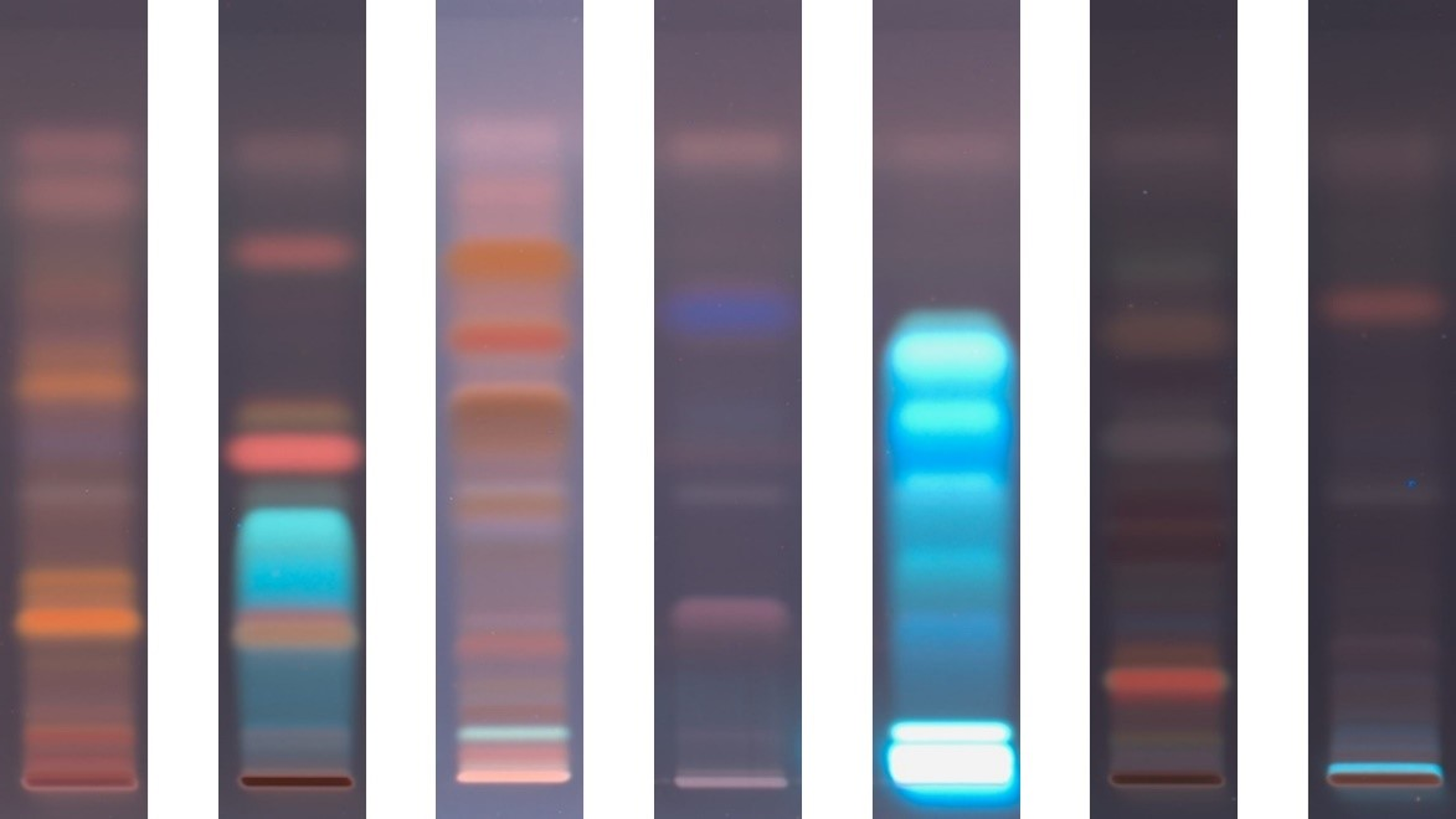

1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method: Images of the plates were documented using the TLC Visualizer 2 in white light after derivatization. A clear zone under a purple background revealed the presence of an inhibitor.

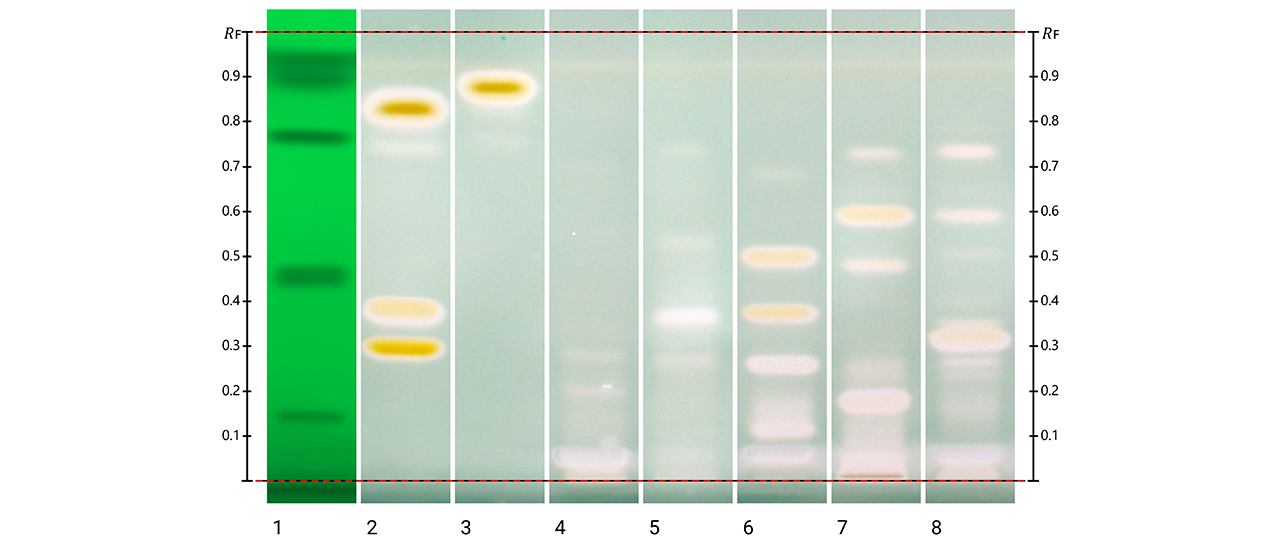

4-MU acetate method: Images were documented using the TLC Visualizer 2 in UV 366 nm after derivatization with 4-MU acetate. The presence of inhibitors was revealed as non-fluorescent (dark) zones against a bright fluorescent background. Images were processed using ImageJ software (for negative peak area measurement).

Densitometry

1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method: Fluorescence measurement is performed with the TLC Scanner 4 and visionCATS at 533 nm (tungsten lamp) without cut-off filter, slit dimension 5.0 mm x 0.2 mm, scanning speed 5 mm/s.

Results and discussion

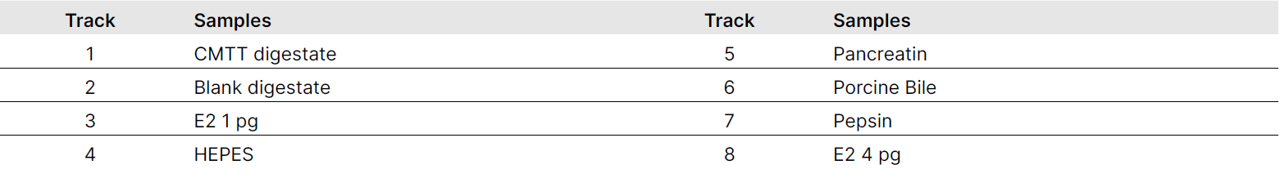

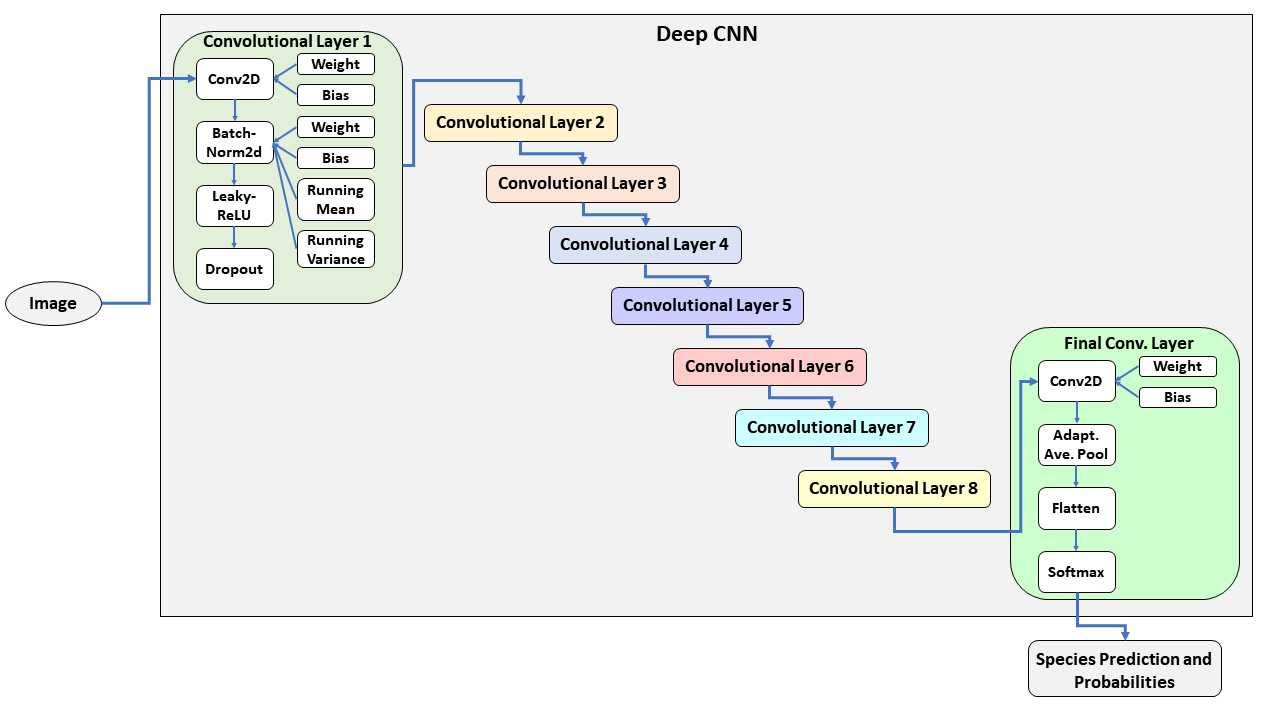

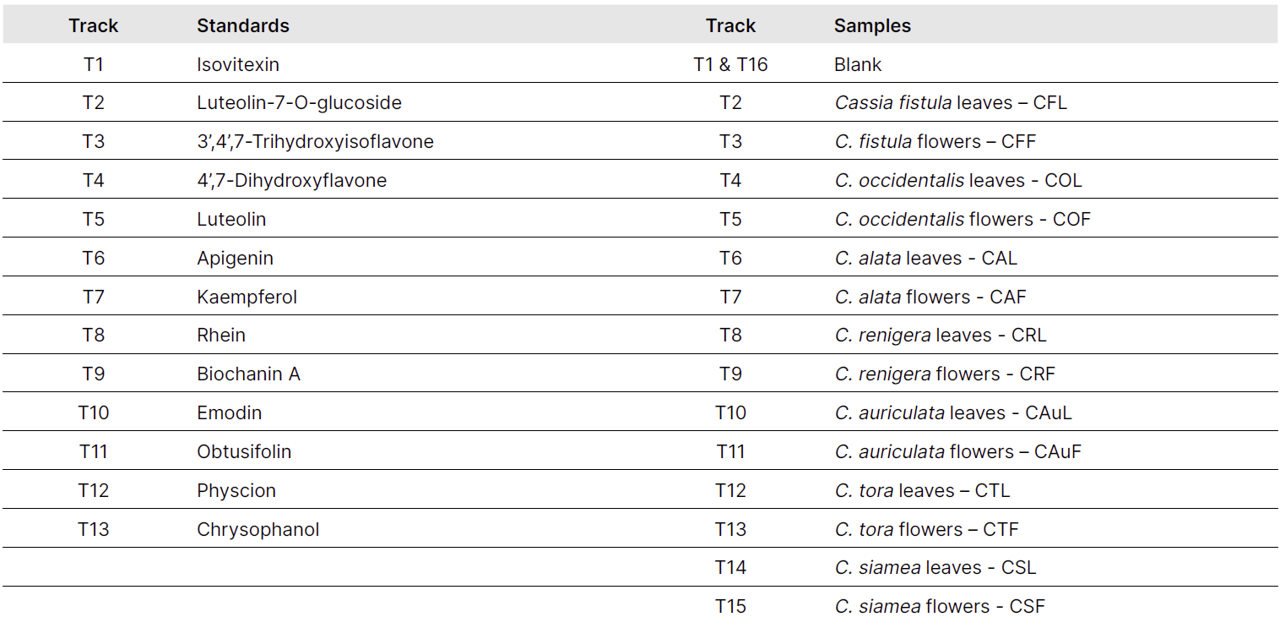

To evaluate the performance of the new probe, the 4-MU acetate method was compared to the traditional 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method using galantamine as a reference standard.

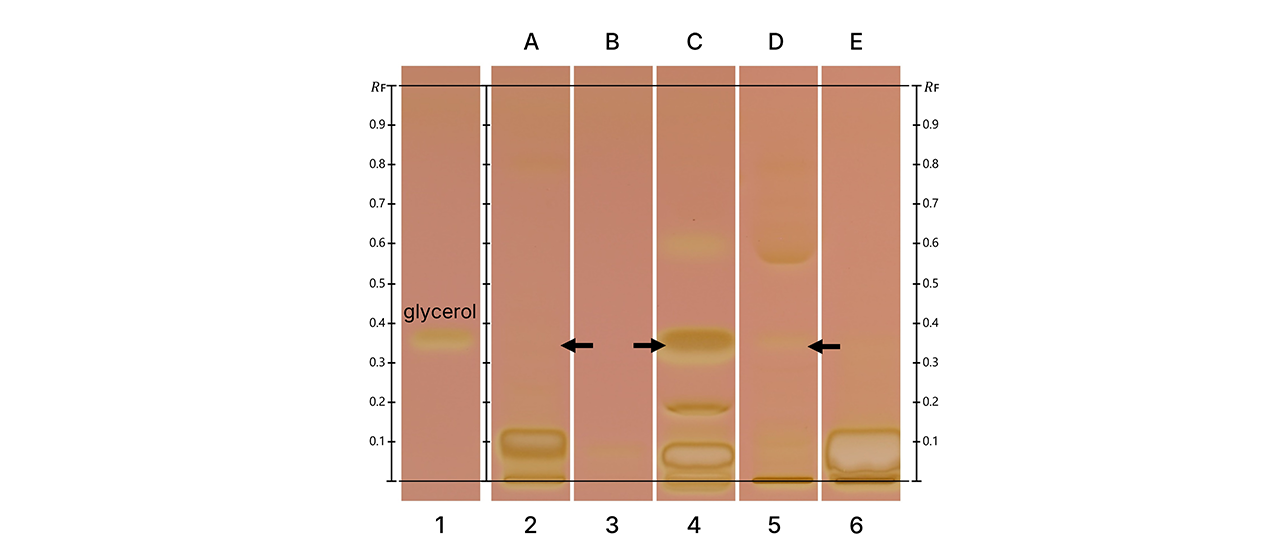

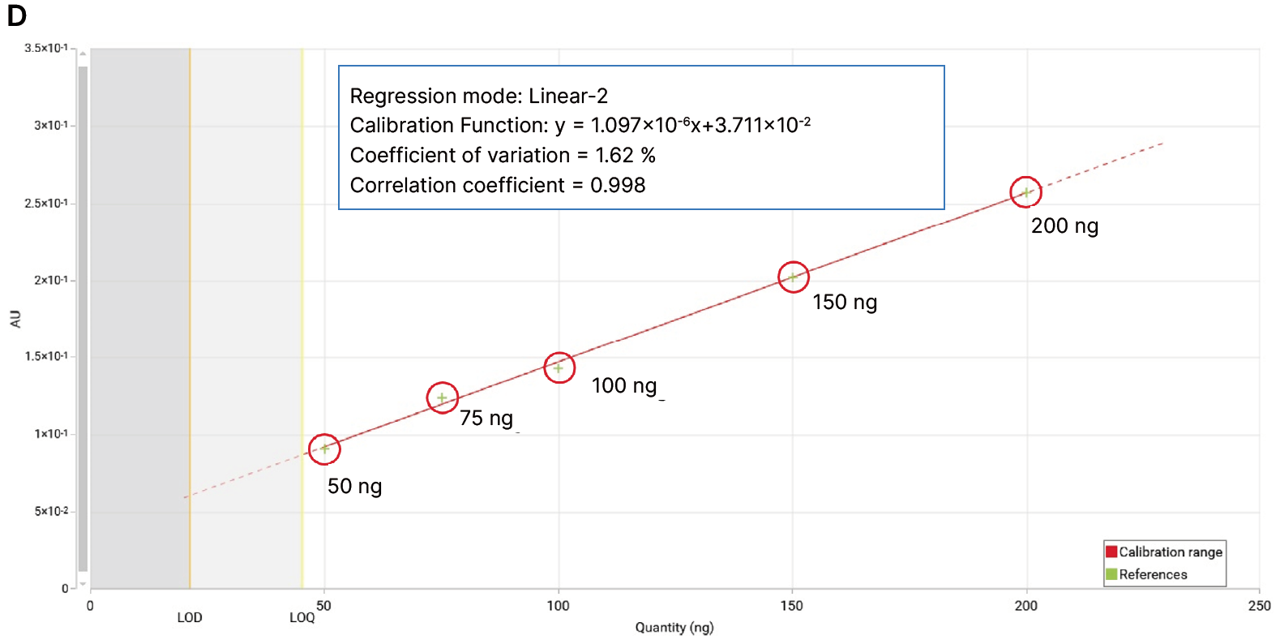

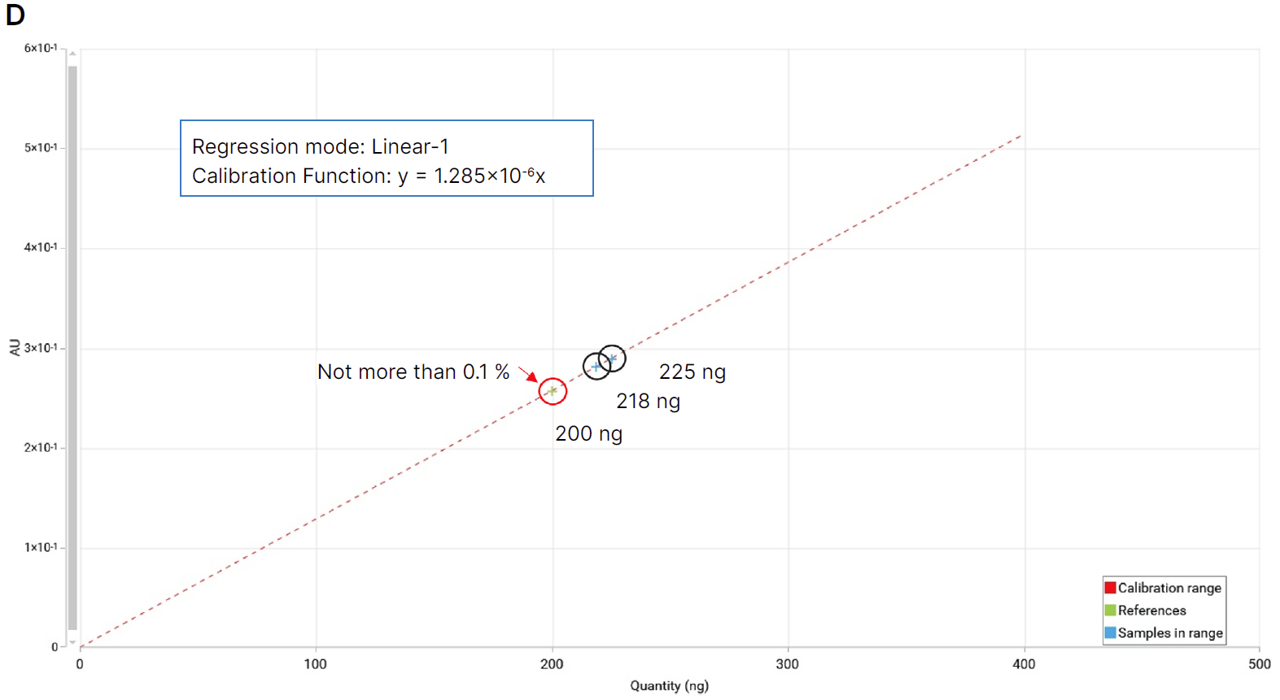

The 4-MU acetate method demonstrated a significant improvement in sensitivity, achieving a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.29 ± 0.02 ng/band and a limit of quantitation (LOQ) of 0.95 ± 0.06 ng/band. In contrast, the classical FBS method yielded an LOD of 0.93 ± 0.05 ng/band and an LOQ of 3.09 ± 0.18 ng/band, confirming a sensitivity improvement of more than threefold.

Precision was high, with relative standard deviations (RSD) between 10 % and 15 %, which is remarkable given the nanogram scale of the analytes, in accordance with Horwitz’s equation.

Linearity ranges were similarly close for both methods: 5–50 ng/zone for the 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method and 2–20 ng/zone for the 4-MU acetate method, each covering a tenfold range above the lowest quantity tested.

Comparison of calibration curves for 4-MU acetate and 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS. Normalized intensity is plotted against applied quantity (ng/zone). Linear regression parameters and corresponding LOD and LOQ values are indicated for each substrate.

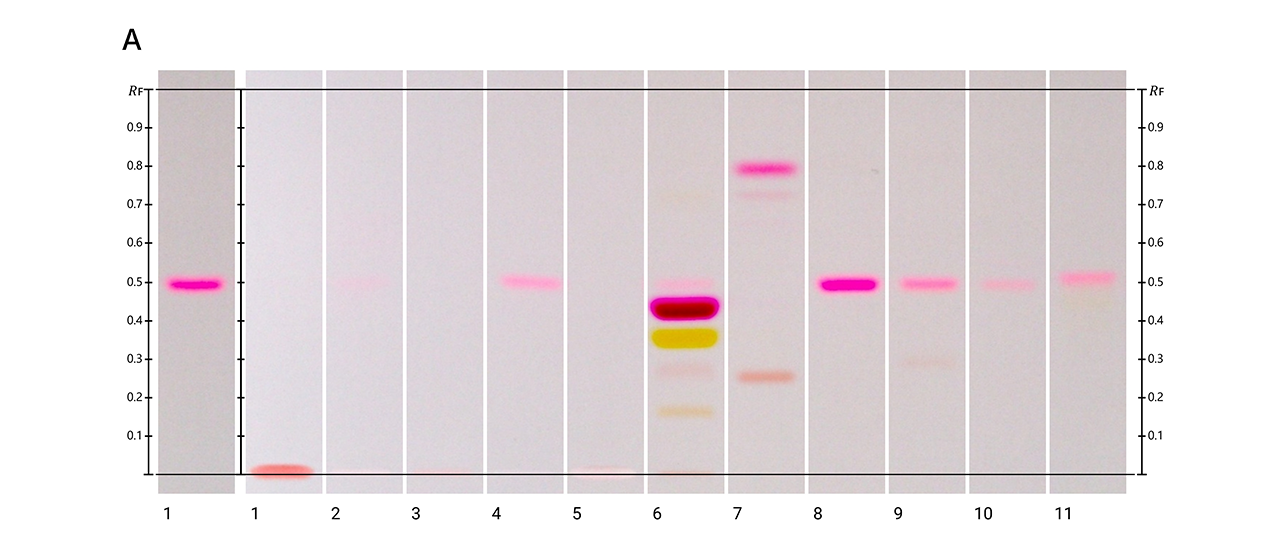

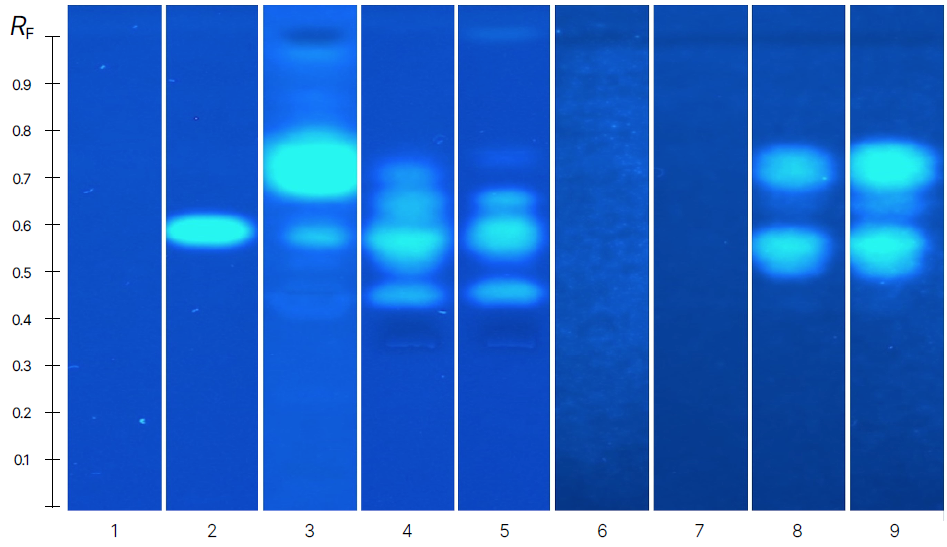

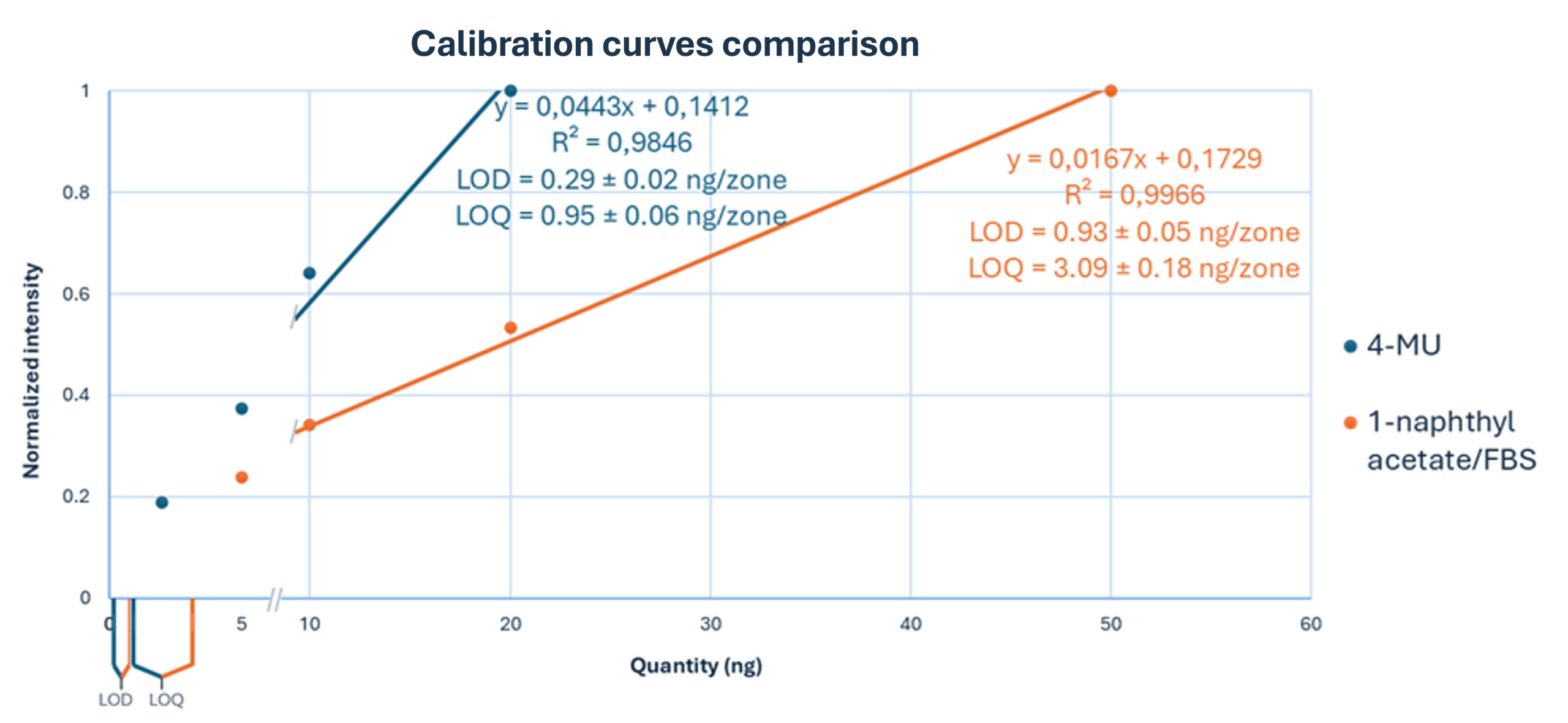

With the 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method, complex matrices can generate both false positives and false negatives, as phenolic compounds may form the same purple azo dye independently of enzyme activity. Although protocol adaptations can reduce this effect, interpretation remains challenging. In contrast, the 4-MU acetate method avoids most false negatives because fluorescence only appears after enzymatic cleavage. Potential false positives using the 4-MU acetate method, due to quenching or absorption at 366 nm, were not observed in our samples and can be minimized through probe optimization in future work. Several mushroom extracts showed clear inhibition zones with the 4-MU probe, while no activity appeared using the 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method, typical false negatives arising from its lower sensitivity. At higher loads (100 μg/track), the 1-naphthyl acetate/FBS method also showed coloured matrix-derived zones unrelated to enzyme inhibition, indicating false positives. None of the compounds detected with the 4-MU acetate method absorbed at 366 nm, confirming its low susceptibility to false positives.

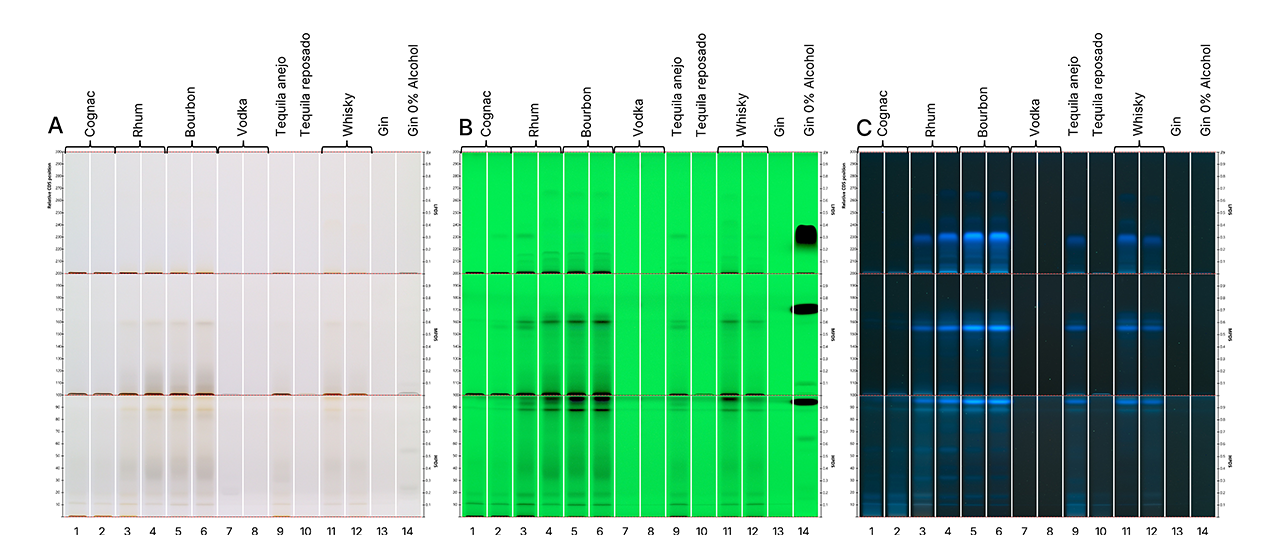

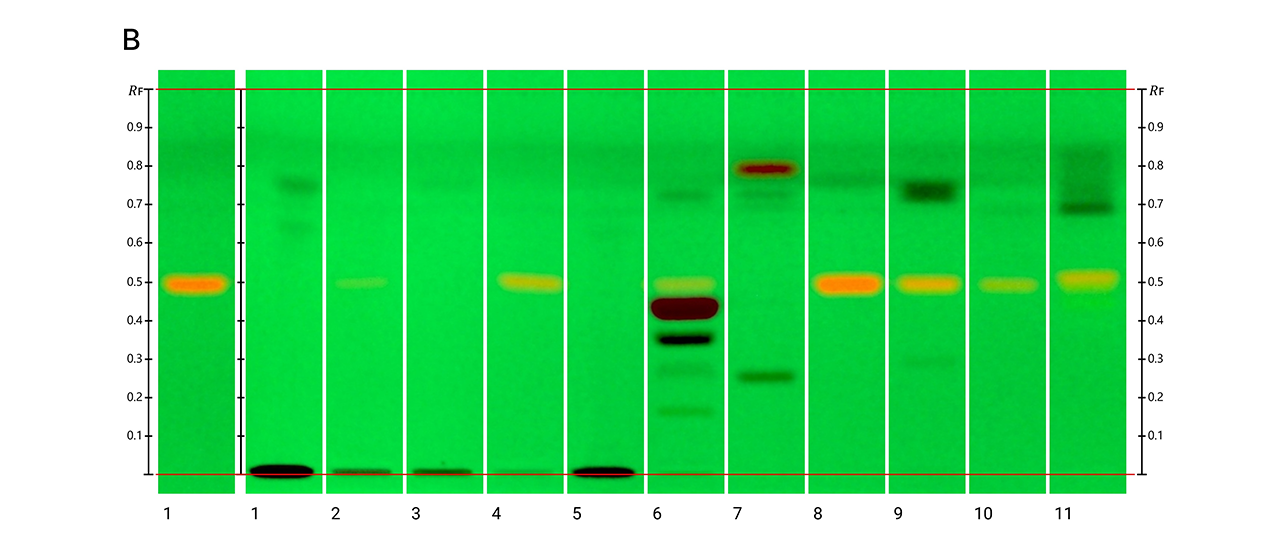

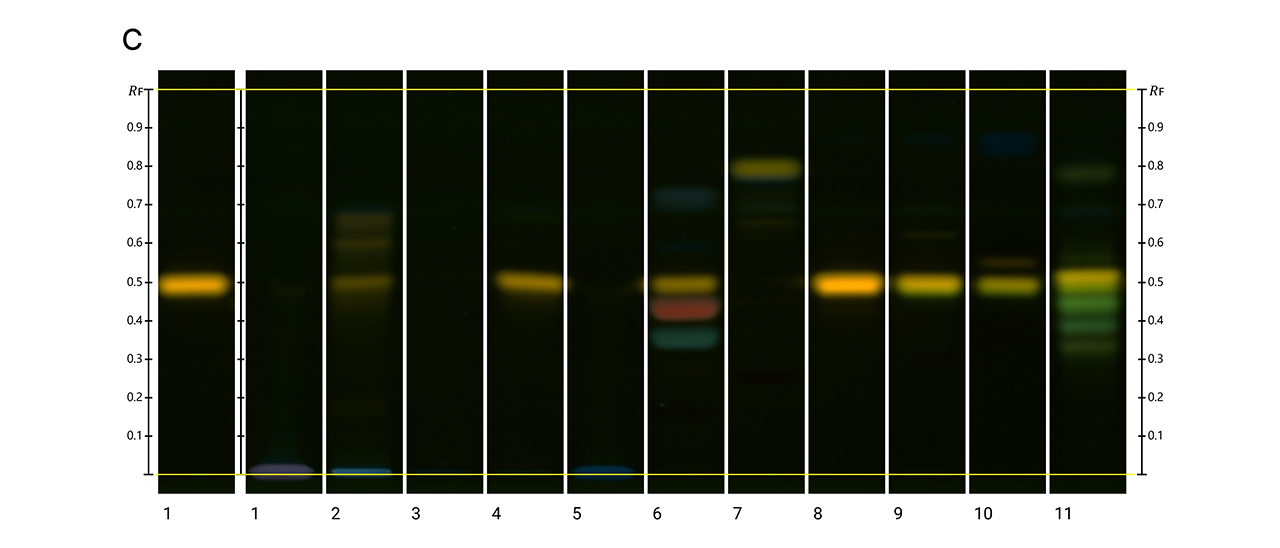

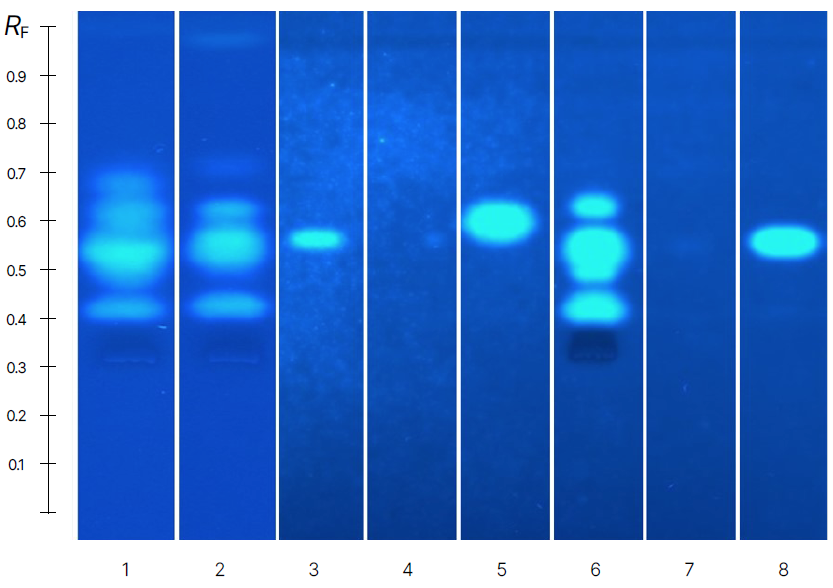

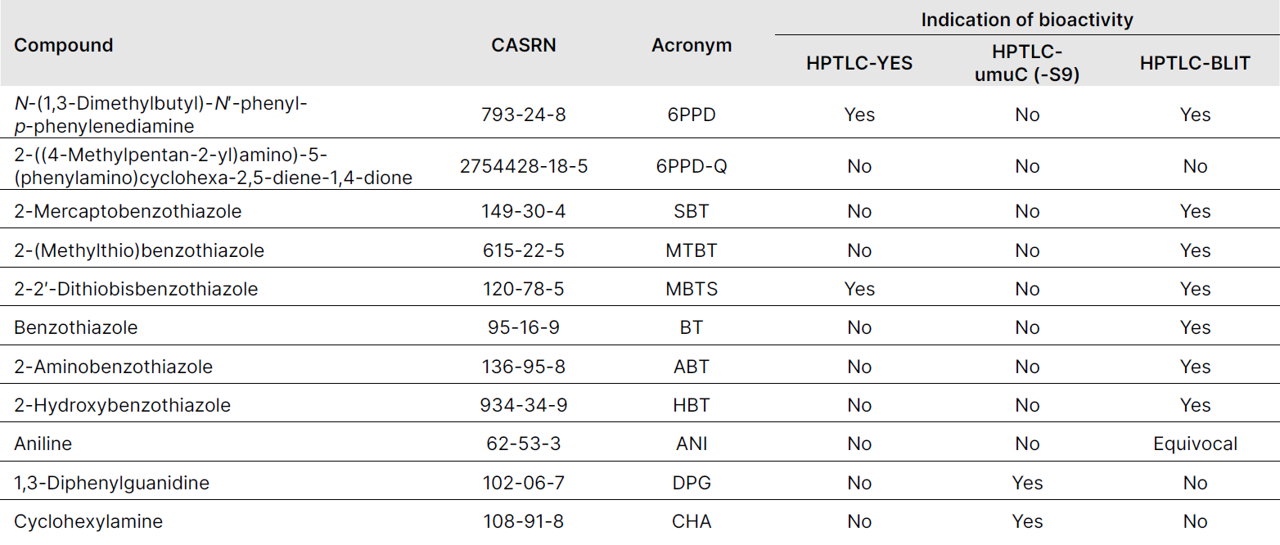

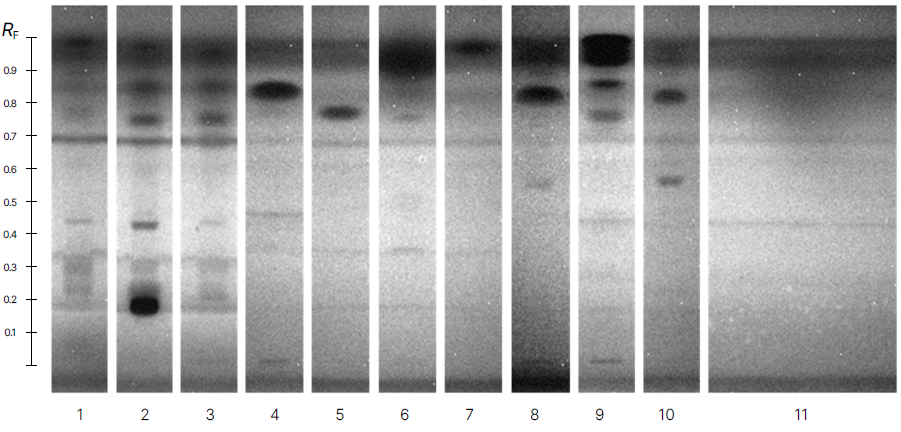

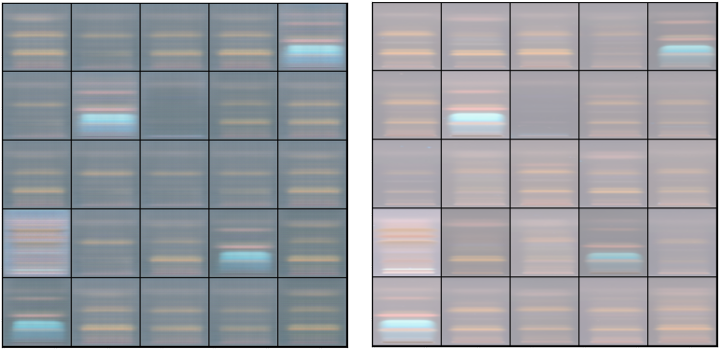

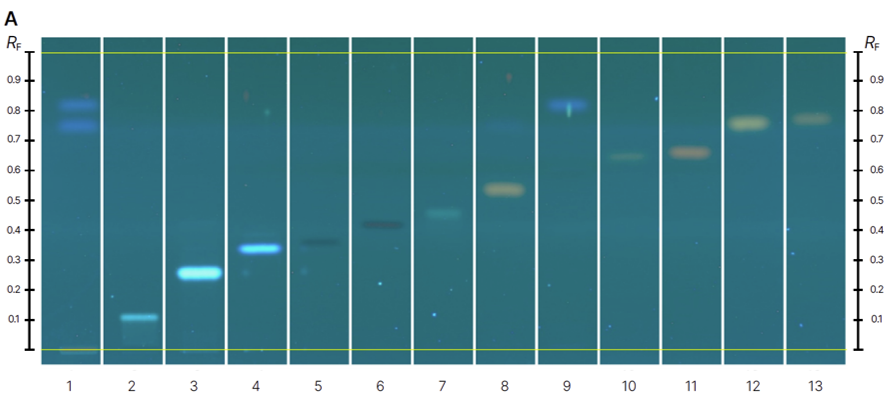

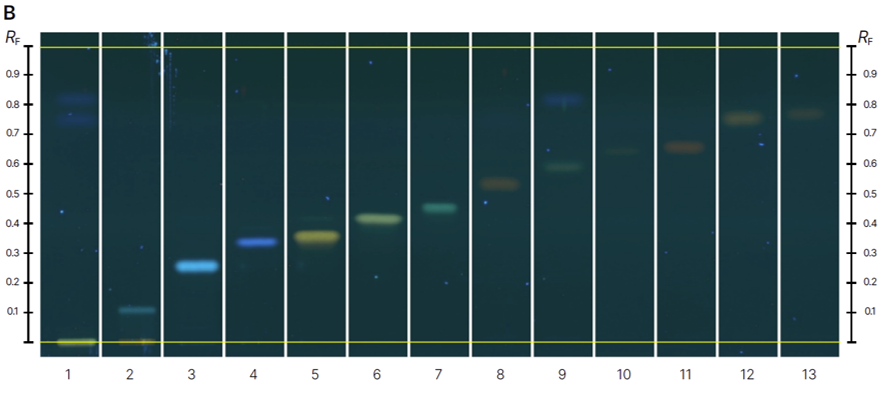

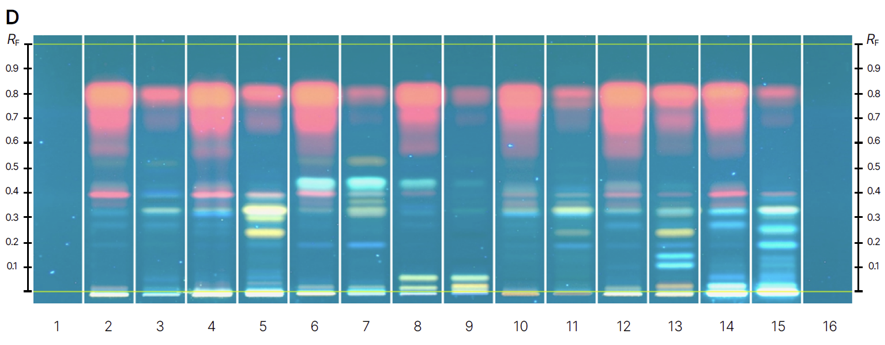

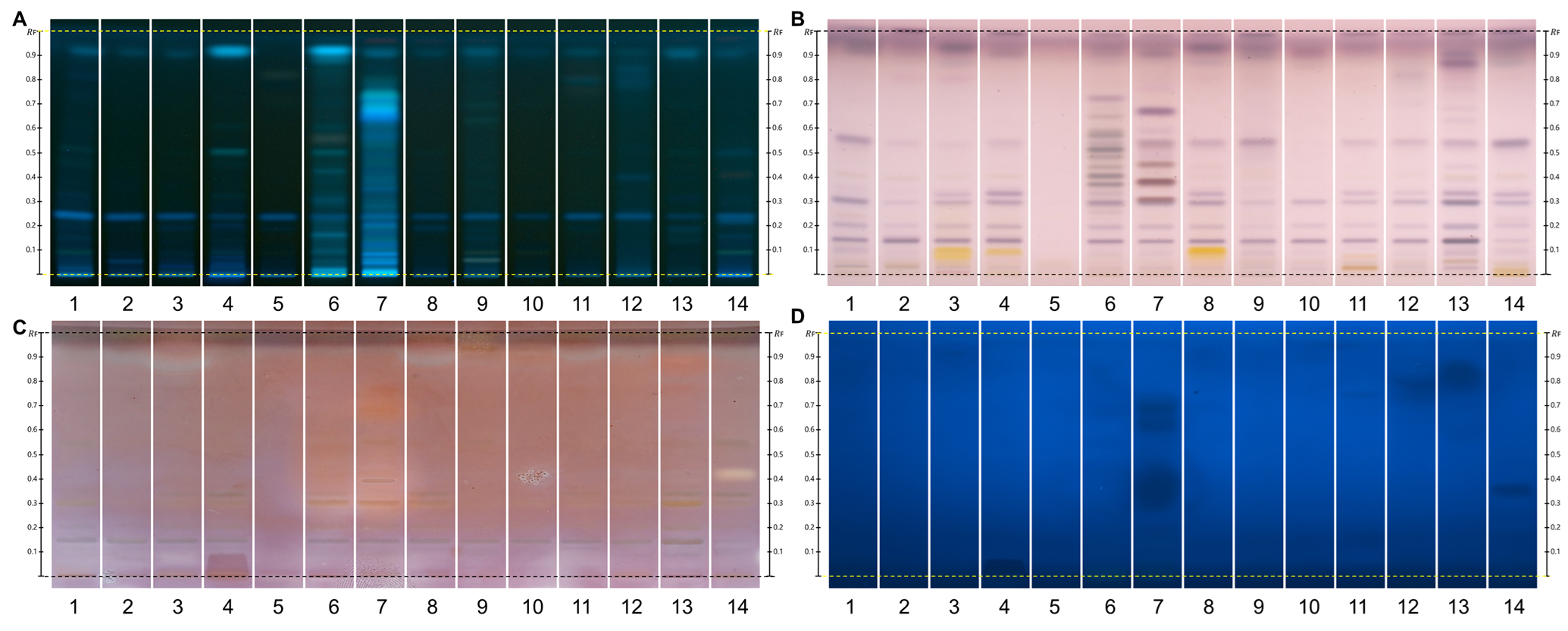

HPTLC fingerprints of the crude mushroom extracts and their fractions visualized under four detection conditions. (A) UV 366 nm prior to derivatization, (B) p-anisaldehyde post-derivatization, (C) naphthyl/FBS post-derivatization, and (D) UV 366 nm after derivatization with 4-MU acetate. Track 1: Agaricus silvicola; 2: Amanita muscaria; 3: Amanita phalloides; 4: Cortinarius orellanus; 5: Grifola frondosa; 6: Gymnopilus penetrans; 7: Hypholoma fasciculare; 8: Laccaria amethystine; 9: Lactarius blennius; 10: Lactarius subdulcis; 11: Tricholoma auratum; 12: Tricholoma saponaceum; 13: Tricholoma ustale; 14: Xerocomellus chrysenteron.

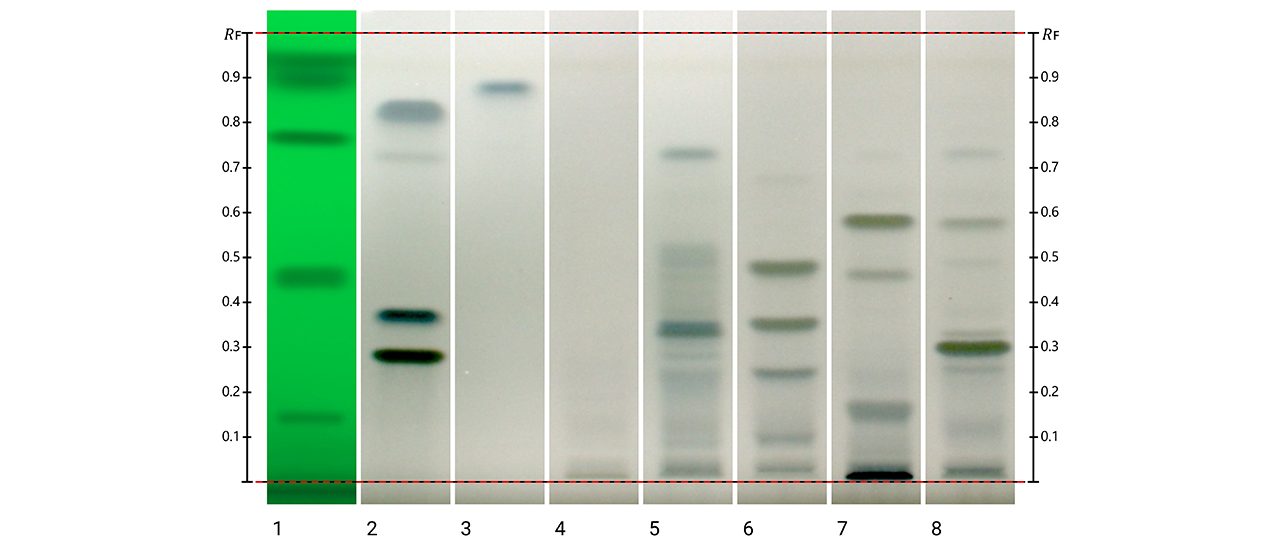

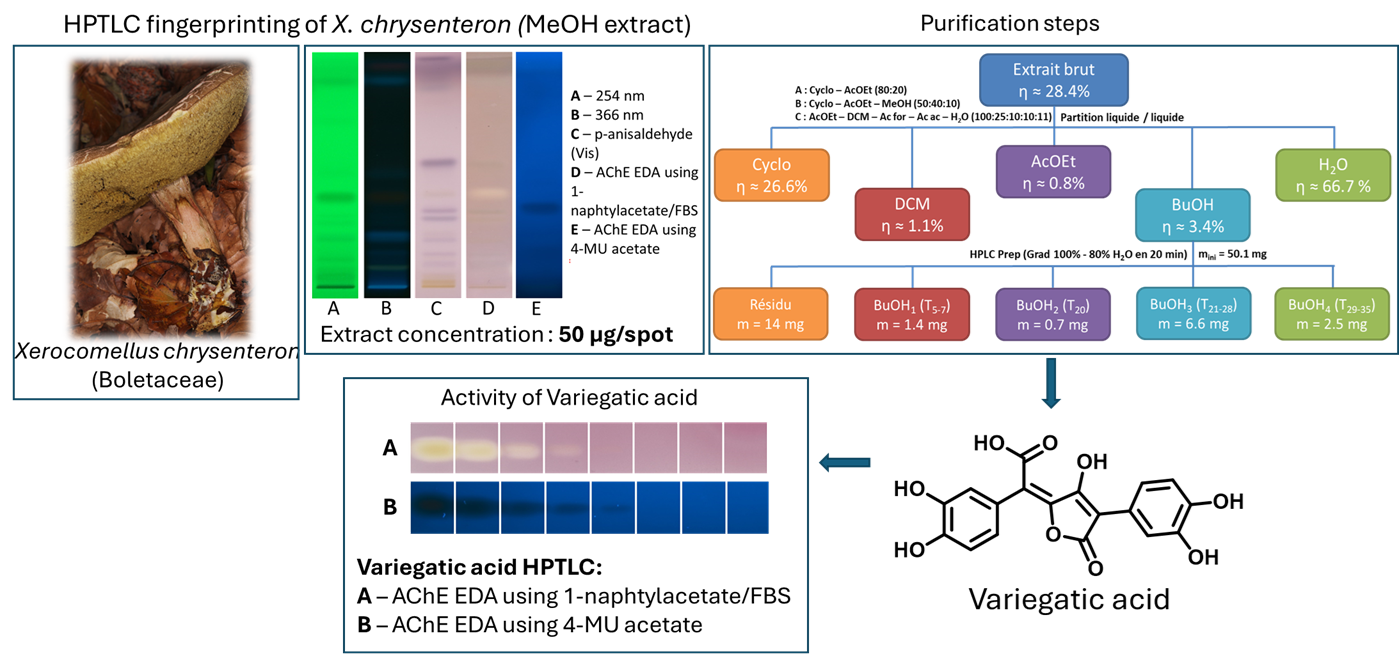

The extract of Xerocomellus chrysenteron displayed a strong AChE-inhibiting band under both detection methods. Purification of the active zone led to the isolation and identification of variegatic acid. The 4-MU acetate method additionally revealed weaker activities not visible with the chromogenic method, demonstrating its higher sensitivity. This example shows how the fluorescent probe improves detection while reliably guiding the isolation of genuine bioactive compounds.

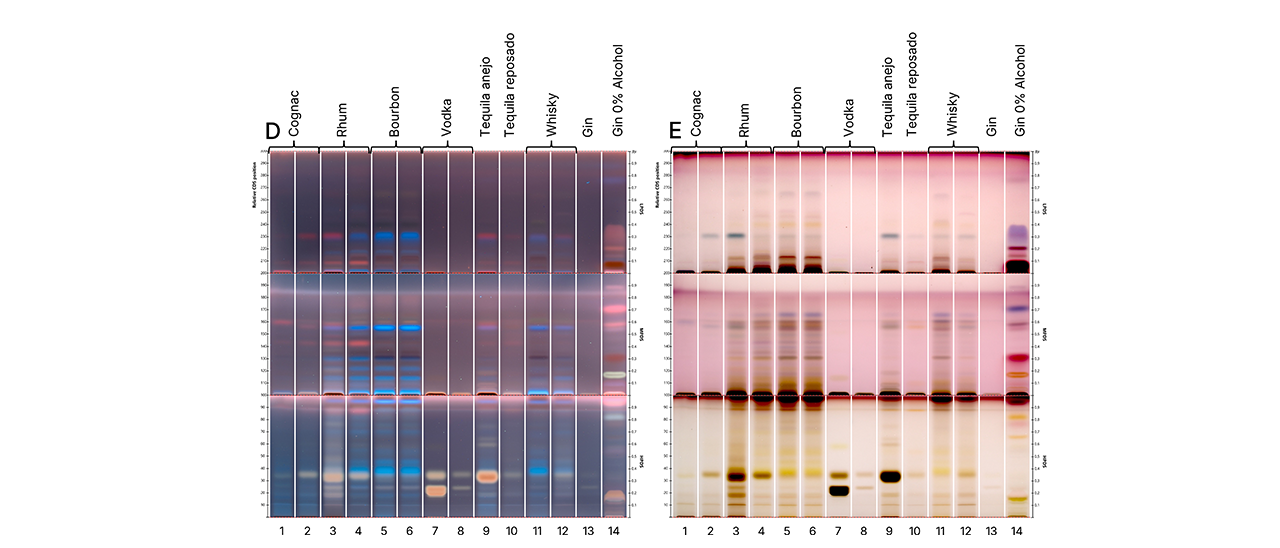

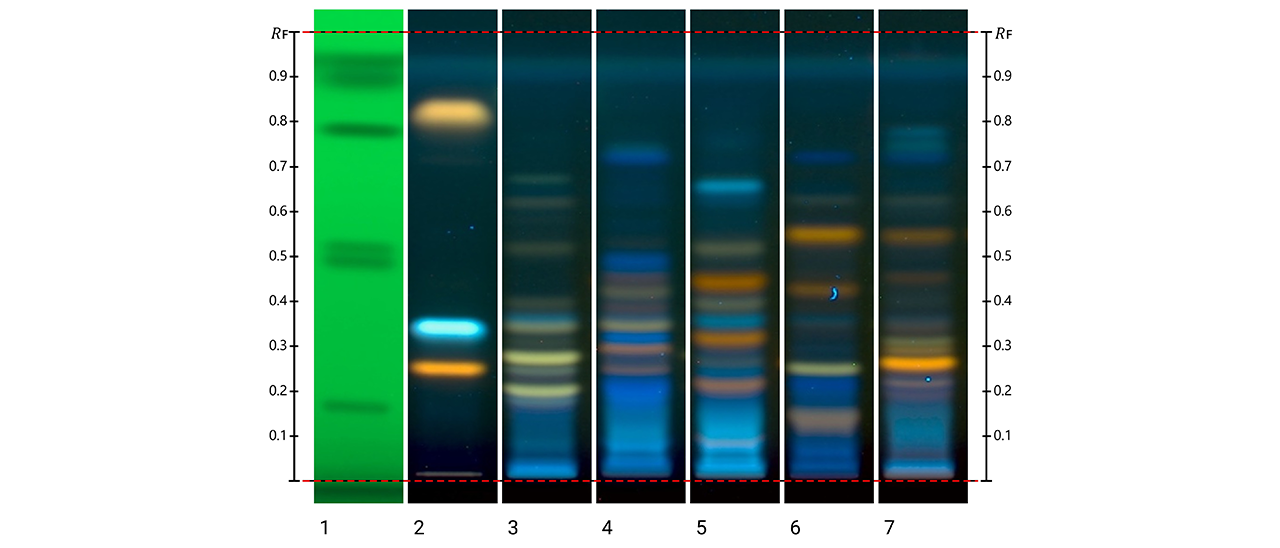

Overview of the extraction and fractionation strategy used for X. chrysenteron mushroom material, with corresponding HPTLC fingerprints. The crude extract was separated into five solvent fractions and further sub-fractionated, with detected metabolites visualized by HPTLC under multiple detection modes.

Conclusion

This work presents a new HPTLC-EDA method utilizing a 4-MU-based fluorogenic probe and compares it to the classical chromogenic assay using AChE as a model. The fluorescent method provides a higher sensitivity, fewer artefacts, and robust performance. Used together, both methods provide reliable AChE inhibitor screening. Owing to its simplicity, low cost, and high sensitivity, this approach can be extended to other enzyme targets and represents a promising tool for future bioactivity-guided screening.

Literature

[1] Gainche M. et al. J Chrom A 1708 (2023) 1

Contact:

Elodie Jagu, Université Clermont Auvergne, 63001 Clermont-Ferrand, France, elodie.jagu@sigma-clermont.fr

Maël Gainche, Université Clermont Auvergne, 63001 Clermont-Ferrand, France, mael.gainche@sigma-clermont.fr